The most recent edition of Credenda Agenda is chiefly about Flannery O'Connor. An article that struck me the most was Peter Leithart's Why Evangelical's Can't Write. His thesis:

The most recent edition of Credenda Agenda is chiefly about Flannery O'Connor. An article that struck me the most was Peter Leithart's Why Evangelical's Can't Write. His thesis:Here is a thesis, which I offer in a gleeful fit of reductionism: Modern Protestants can't write because we have no sacramental theology. Protestants will learn to write when we have reckoned with the tragic results of Marburg, and have exorcised the ghost of Zwingli from our poetics. Protestants need not give up our Protestantism to do this, as there are abundant sacramental resources within our own tradition. But contemporary Protestants do need to give up the instinctive anti-sacramentalism that infects so much of Protestantism, especially American Protestantism.

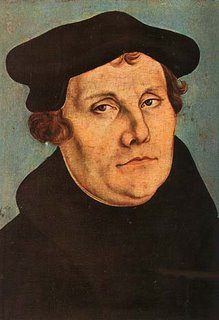

The reference above to Marburg is there because Leithart opens his article with the 1529 Colloquy at Marburg where Zwinglians and Lutherans met to debate and come to an agreement on Luther's doctrine of the real presence in the Eucharist. After agreeing to fourteen of the fifteen propositions put forth by Luther, the Zwinglians--once they were home, after the colloquy--took up the cudgels once again for the Eucharist as mere memorial and the Lutherans once again fought back with their real presence position.

Leithart's argument for why evangelicals can't write goes back to this historical occasion. When the Zwinglians and Lutherans finally parted ways for good at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, the Protestant mind would forever be influenced by the rift:

Marburg is important not so much for what it achieved but as a symbol of what it failed to achieve. It provides a symbolic marker not only for the parting of the ways between Lutheran and Zwinglian, but also, for Zwinglians, the final parting of the ways between symbol and reality. J. P. Singh Uberoi claimed that "Spirit, word and sign had finally parted company at Marburg in 1529. For centuries, Christian sacramental theology had held symbol and reality together in an unsteady tension, but that alliance was ruptured by the Zwinglian view of the real presence. For Zwingli, "myth or ritual . . . was no longer literally and symbolically real and true." In short, "Zwingli was the chief architect of the new schism and . . . Europe and the world followed Zwingli in the event."

For many post-Marburg Protestants, literal truth is over here, while symbols drift off in another direction. At best, they live in adjoining rooms; at worst, in widely separated neighborhoods, and they definitely inhabit different academic departments.

No comments:

Post a Comment